Matrifocal homes in Laos

In Australia, homelessness and domestic violence feed one another, contributing to the survival of misogyny-as-usual. In another corner of our world another reality already exists.

This is the fourth and final part in a four-part series looking behind the scenes of near universal home ownership in Laos. In Part One, I pointed out that Laos has some of the highest home ownership rates in the world, in Part Two, I looked at the socialist policies contributing to those rates. In Part Three, I linked high home ownership rates to the demands of small-scale family farming. In this post, I look at home ownership in relation to the status of women in Laos. Laos is far from a patriarchy-free utopia, but it does provide glimpses of alternate ways of living that avoid the insidious link between domestic violence and homelessness so ingrained in the Anglophone world.

In an earlier post, I introduced a woman I call Mercy, the Lao woman who took me in when I lived in her village, a woman I call ‘mother,’ and whose family I know best in Laos. I pick up her story again here.

Once, I showed Mercy’s family a picture of my home in Australia—actually, it was not my home but the home my mother was living in at the time. It is an historic home: pretty, in an oldy worldy nostalgia kind of way. This was ages ago, when Mercy’s daughter Suay was still alive. Suay said she wished she could live in such a home. But Mercy said she would never want to live in a house like that: with such thick walls, no one could see or hear what was going on inside. Specifically, she said ‘I would never want to be a woman in a house like that.’ I have thought of her comment often over the years since, as Australia’s domestic violence crisis continues to intensify.

Mercy is ethnic Lao, and in her village households are usually headed by women. Ethnic Lao make up approximately half of Lao PDR’s population. Although the government continually emphasises the multi-ethnic character of Laos, ethnic Lao hold disproportionate cultural force in the country. In Mercy’s village daughters inherit rice fields, and this is typical for ethnic Lao. The youngest daughter cares for her aging parents and inherits the family home. Her older sisters typically move out some time after marriage (after a period of matrilocal residence where the son-in-law contributes to work on his parent’s-in-law farm). Often, these sisters move out into homes built nearby on land gifted from their mother, so that clusters of married sisters tend to live nearby one another. Their brothers claim their inheritance—buffalo and cows—at marriage when they move away to be with their wives and their families. This form of inheritance and residence is not enforced in law and it is not followed by all ethnicities in Lao (the Family Law in fact dictates formal equality between men and women). However, as the norm among the numerically and culturally dominant ethnic Lao, it does exert a moral force that is felt throughout Laos.

In Lao homes, the (female) household head leads the veneration of household spirits: at death, a female household head becomes a household spirit. During courtship and after marriage, a son-in-law may pay fines to the household spirits (in a ritual known as ‘repair to the house’) if he transgresses the rules of the house, such as a pregnancy before marriage, speaking harshly to his wife, or chastising his wife without her parent’s prior permission. Lao legal scholar and historian, Mayoury Ngaosyvathn reflects that this, combined with the practice of matrilocality after marriage, ‘tames the husband’.1

Mayoury theorises ‘dialectic themes of oppression-liberation’ in gender dynamics in Laos.2 On the one hand, a deep history of matriarchal power continues, evident in women’s continued authority in animist rituals, familial decisions and agriculture. On the other hand, since the 11th Century, Buddhism and Indic influences introduced patriarchal structures that denigrated women symbolically, politically and legally. Legal codes and folk tales developed a set of rules for women’s behaviour, some of which seem bizarre: for instance, a woman should bathe her husband’s feet before bed each night, always be the last to sleep and the first to rise, and ritually prostrate herself before her husband to apologise for any misdemeanours each Buddhist holy day (the women I know don’t do this, but the image persists). The socialist revolution in 1975 entailed an ambitious program of female liberation, but the dialectic between oppression and liberation continued. Despite the socialist ideal of equality between men and women, women continue to shoulder disproportionate household work as well as ideals of feminine behaviour. In fact, this is a third meaning of ‘family economy’ (a phrase I have explored in earlier posts): for Mayoury, ‘family economy’ is a phrase associated with the pressure for women to leave the civil service so that men’s jobs could be protected during the economic upheavals of the 1980s.

My take on the extreme veneration of the husband, coupled with the everyday fact that women run the actual household on a practical level, is that men are treated as honoured guests. In marriage ceremonies, when the groom arrives at the bride’s home, female relatives of the bride playfully block his entry, only granting entry when his party bribe them with a little alcohol and perhaps some cash. The groom represents a potentially unruly outside force to be tamed, but one necessary for the continuance of the household. I have observed that if a woman dies young, often her widowed husband will move out to join a new wife (leaving his children) rather than go on living with his mother-in-law, underlining the guest-like place men hold in matrifocal homes. Men are important—even honoured and served with much ado and great pomp—but they come and go, whereas women are the continual line between generations. Like guests, husbands receive special treatment largely because they don’t really belong.

Figure 1: A female homeowner watches her great grandchildren eat.

In rural Laos, houses are usually built on stilts from wood or bamboo with grass thatch, or perhaps aluminium or tile roofing. The dichotomy in a Lao house is not so much inside versus outside, as upstairs versus downstairs. Most cooking, evening dining, hosting formal guests, special events, storing of valuables and nighttime sleep happens upstairs, with shoes left at the bottom of the steps. Most daily life occurs below in the dirtier but cheerful galang underneath the house. Here, fires offer warmth in the cold of the morning and shade offers escape from the heat of the day. Rice threshing, milling, daytime naps, tool maintenance, handicraft production and visits from familiar guests occur here. Children are birthed in the galang and a new mother sits out her postpartum period of rest there. The galang opens onto gardens, fruit trees, granaries and outhouses. Chickens peck around.

Figure 2: A female homeowner watches her grandchildren on Tik Tok in the downstairs galang part of her house.

All houses in Mercy’s village perch between river and rice fields. Neighbours are close but not intrusively so. Fences are used more for keeping livestock out of gardens than for marking territory. A dirt path weaves from house to house around the shore and across the rice fields, sometimes passing close by, even under, houses. If no one is visible in the galang, passersby still call out a friendly greeting, in case someone is upstairs. The usual is ‘have you eaten rice yet?’ If someone is home, they will reply with a comment about food, or perhaps an invitation to join a meal. Sound carries easily through the thin walls, even when people are upstairs and out of sight. At first I thought this was an unfortunate outcome of poverty in building materials, but Mercy invited me to look at the permeability of Lao homes as a deliberate design choice, one with important consequences for women.

Rural ethnic Lao homes offer privacy, but this is not the enclosed, even airtight, variety that is increasingly popular in the architecture of Western Europe and the Anglophone world. It is a privacy tempered by a strong accent on social integration. Lao sayings and habits indicate that aloneness is undesirable, while being part of a group is healthy. For instance, it’s often said that meals eaten alone taste bland. Many people I know in rural Laos never experience sleeping even one night alone. They say farming rice alone isn’t possible, and given the centrality of rice to life itself, this is a way of saying living alone isn’t possible.

Of course circumstances sometimes mean that people do end up sleeping, eating, working or living alone, but this isn’t a common or valued state. People prefer to live, work, eat, sleep and live in groups. The massing together of people signals health and wealth. When people do fall ill, curing rituals—both among the ethnic Lao as well as other ethnic groups—typically involve massing people together around the ill person. At death, again, people mass in the bereaved family’s home for the night. When I collected birth stories on Mercy’s island, a recurring feature was the great number of people who attended the birth: the more the better it seemed in some women’s recounts, with proud descriptions of how full their homes were as they laboured. Birthing, eating, illness, sleeping and dying—all times when people mass together in Laos—are also moments when the permeability of the body is hard to ignore.

Like houses, bodies can be closed or open, sealed off or mingled. Mikhail Bahktin, Russian philosopher and literary critic, argued in Rabelais and his World (his WWII-era PhD thesis) that the open, permeable body was symbolic of reversals of the usual hierarchical order in Medieval Europe. The Middle Ages are usually remembered as a period of religious austerity and stiff hierarchy, but Rabelais (a popular author of the Renaissance) wrote of the Middle Ages as a time of gluttony, improbable births, lust, carnival and coarseness. Bahktin suggested Rabelais captured a stream of popular culture that peaked in the Middle Ages and, by the Renaissance, was already under pressure. This popular culture, and how it sat alongside everyday hierarchy, is perhaps most familiar to current day readers in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, which veers between severe religious imagery and festival-like playfulness.

Figure 3: The Battle between Carnival and Lent, by Hieronymus Bosch. WikiCommons.

Anthropologist David Graeber drew on Bahktin’s analysis of the Medieval movement between formality and carnival, and combined it with the observations made by numerous anthropologists of extreme ‘avoidance’ style relationships and mandatory ‘joking’. Avoidance relationships were very formal, as when a son-in-law may be prohibited from looking at or speaking with his mother-in-law. ‘Joking’ relationships, by contrast, might oblige a grandfather and grandson to swear at one another and grab at one another’s genitals. Avoidance relationships are characterised by feelings of shame and deference, while joking relationships cause laughter and euphoria.3 Anthropologists observed relationships along these lines in the Americas, Africa, the Pacific and Australia.

Reading across these numerous examples, Graeber proposed a continuum that may be present in all human societies. On one extreme, ‘avoidance behaviours’ are the kind of decorum required for formal situations. The permeability of the human body is symbolically downplayed, for instance by discretely masking bodily orifices or confining bodily secretions to private, off-stage spaces. Graeber argues that the closed body indicates social distance, even hierarchy. At the other extreme one finds ‘joking behaviours’ where the permeability of the body is not only acknowledged but given vulgar or profound importance. Joking behaviours are characteristic of egalitarian relations. A fart among friends draws laughs. Not so in front of the boss.

Graeber argues that, viewed across cultures, this continuum is related to varying concepts of property. In some cultures, the ‘owners’ of a species, food or place are strictly forbidden from contact with what they ‘own.’ This seems at first glance very different from liberal democratic concepts of private property, where an owner is imagined at full liberty to consume, use or otherwise dispose of what they own, but Graeber argues that the underlying similarity is avoidance. C.B. Macpherson detailed the possessive individualist concepts of ownership developed under liberal democracies where an owner is the person who has the right to use, consume or dispose of what they own to the exclusion of all others.4 Property under liberal democracies remains a social relation whereby some have access and others avoid, but in this case it is the owners who access and non-owners who avoid.

Graeber argues that with the rise of possessive individualism since the seventeenth century, behaviours that were once only required under ‘relations of formal deference’ gradually came to ‘set the terms for all social relations, until they became so thoroughly internalized they ended up transforming people’s most basic relations with the world around them’ (2007, 31). That is, behaviours once appropriate only to a limited range of relations became generalised across everyday sociality when ideas of property and ownership became generalised and ingrained in ideas of what it is to be a person. Our property conceptions are evident in the minutia of please’s and thank you’s, personal dress, bodily presentation, and arrangements of bodies in public versus private spaces.

I believe Graeber’s ‘generalised avoidance relations’ can be seen in housing in liberal democracies. There is a tendency in Australia to imagine homes as closed off, even ‘airtight’ spaces. This is implicit in the classic Australian quarter acre block with fenced off yard and free-standing, double brick structure. It is there, too in the more recent trend for ‘passiv haus’ style energy efficient homes: tight seals around thickened orifices (the doors and windows) promise to control even of the air which passes in and out of a home. Such views of homes are not just an architectural trends: they are cultural ideas fixed in bricks and mortar.

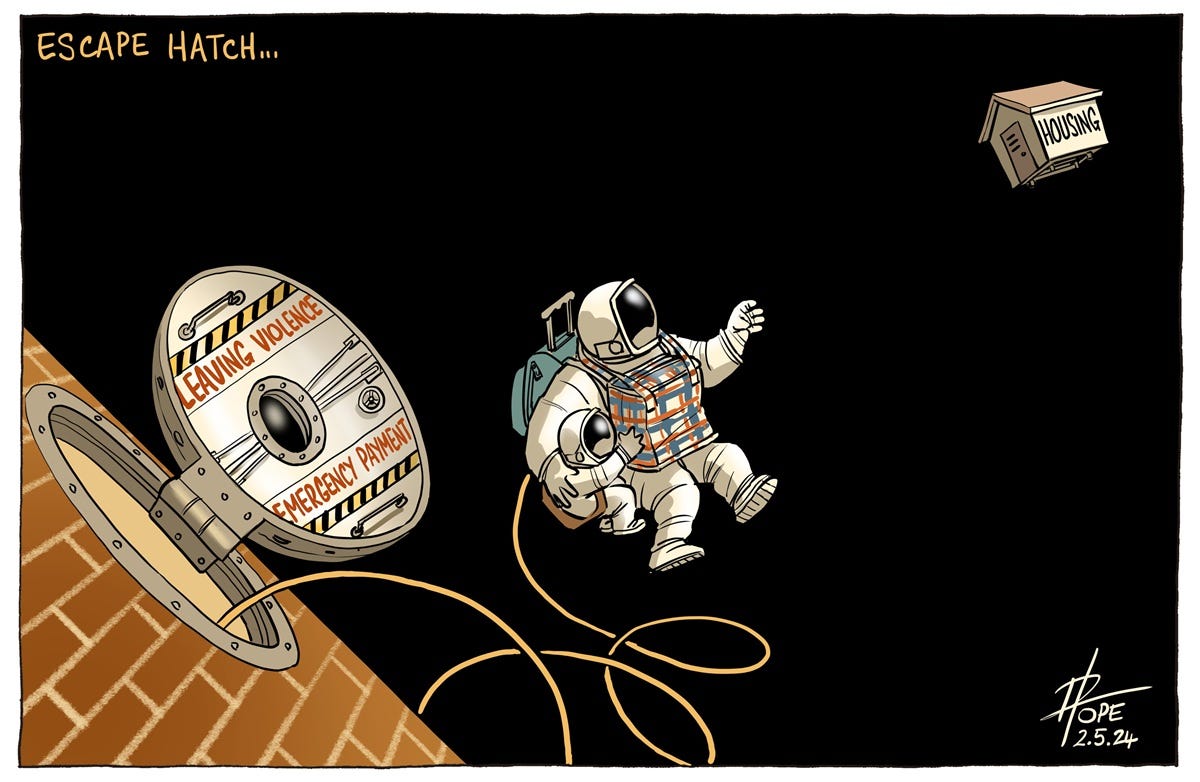

And we know these ideas have tangible impacts on how people live. The drawing in Figure 4 by David Pope was featured in the Australian newspaper The Canberra Times in 2024. It depicts a woman escaping from domestic violence through the metaphor of a space walk. The woman, child in tow, must leap from one ‘airtight’ home (a brick structure/spaceship) to another. Unfortunately, the alternative home she is aiming for drifts out of reach across a dark and empty void. Australian historian and feminist Anne Sommers wrote a caption for this image: ‘Escape hatch: Facing the woman and her child is often a pitiless void with the goal - a new home - so far away it seems unreachable.’5 The idea of housing here is one of airtight vessels separated by voids of homelessness.

Figure 4: By David Pope, ‘Escape Hatch,’ depicts domestic violence and its consequences in Australia. The Museum of Australian Democracy.

In Australia, there is a clear link between homes and violence against women. Women are most likely to experience physical and sexual violence when they are at home.6 The biggest cause of homelessness in Australia is domestic violence: 45% of homeless women and girls in Australia cited domestic violence as the cause. At the same time, women older than 50 are the fastest growing group experiencing homelessness in Australia.

Statistically speaking, both domestic violence and homelessness are less common in Laos than Australia.7 The World Bank estimates 19% of women in Laos have ever experienced intimate partner violence, as compared to 23% in Australia and 27% globally. Laos’ rate of 19% masks significant differences across regions and ethnicities. Ethnicities that favour patrilineal inheritance and patrilocal residence reportedly endorse intimate partner violence at much higher rates than ethnic Lao, and there is some evidence that resettled villages have higher rates of domestic violence. Mercy’s village is one of the lucky ones that was not destroyed during the war or resettled, so attachments to land and to matrilocal residence patterns have persisted more clearly, likely contributing to lower rates of violence. In my observations of Mercy’s village since 2002, I haven’t recorded a single case of domestic violence. This is not to say that domestic violence does not exist, but there is little to no social licence, and strong social norms discourage would be perpetrators.8

It is difficult to locate statistics on homelessness in Laos: the 2015 census appeared to report zero cases of homelessness even though the streets of the capital city increasingly seem home to a small but visible handful of homeless people. The main discourse about homelessness in Laos relates overwhelmingly to disasters which destroy homes or to resettlement whereby landless families may be allocated residential and farmland in a ‘development village’ or focal sites. Even in these cases, homelessness does not appear to be socially embedded or endemic, as it is in Australia, but rather perceived as a temporary aberration to be addressed through assistance packages.

Among ethnic Lao, homes are not so ‘airtight’ in ideal or reality as in Australia. People, sounds, food, and visitors flow in and out of the home, and this in itself is valued as a sign of connection. Connection is associated with health and wealth. Prosperity, if you like, is not how much space one exclusively owns, but how much one shares with others. In ethnic Lao homes one finds spaces both for privacy and for permeation, for avoidance and for joking relations. The upstairs offers some privacy or formality, but is usually avoided. Downstairs is (even) more permeable and open to the outside world and the site of the more ‘joking’ relations. Mercy valued the openness of her home as a cornerstone of woman-friendly family life. Permeable homes, she intimated, offered some protection to women from the excesses potential in any marriage.

Thinking with Graeber and his observations about permeability and ownership, I’m tempted to say that permeable homes temper the ownership husbands feel over their wives. In Australia, intimate partner violence has continued to spiral even as authorities devote significant resources to the issue, especially gender equity education. Some of the countries with the highest rates of gender equity in the world also have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence, a phenomenon known as the ‘Nordic Paradox’. In Laos, gender equality is an ideal but far from a reality. Still, this small nation offers inspiration on an issue with which some of the richest countries in the world are struggling. The lesson gained from comparison with Laos, I believe, is that domestic violence is fuelled not only by gender ideologies, but also by ideologies of property and ownership, ideologies that find expression in our built environments, manners and family forms.

Mayoury Ngaosyvathn. 1993. Lao Women: Yesterday and Today. State Publishing Enterprise, Vientiane. Page 4.

Mayoury, Page 78.

Graeber, David. Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Oakland and Edinburgh: AK Press, 2007. My examples of joking and avoidance type behaviours are taken from Donald Thompson, 1935. The Joking Relationship and Organized Obscenity in North Queensland. American Anthropologist 37:3 Part 1. pp 460-490, but the literature on joking and avoidance relationships is vast.

Macpherson, C.B. 1962. The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism - Hobbes to Locke. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anne Sommers, May 2024. David Pope. https://www.moadoph.gov.au/explore/behind-the-lines/2024-no-guts-no-glory/in-focus/escape-hatch

ABS, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Home owners and renters. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1301.0~2012~Main%20Features~Home%20Owners%20and%20Renters~129

Domestic violence is detailed in my description of an ethnic Kantu village in Projectland: Life in a Lao Socialist Model Village. I have described temporary homelessness in High, Holly. “THE 2018 DAM COLLAPSE IN ATTAPEU, LAOS: Charitable Donations and the Party-State Thriving on Crisis.” Anthropology Today 35, no. 4 (August 1, 2019): 26–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/45171442. And I have described chronic landlessness in High, Holly. “The Implications of Aspirations: Reconsidering Resettlement in Laos.” Critical Asian Studies 40, no. 4 (December 1, 2008): 531–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710802505257.

All the cases of intimate partner violence that I have recorded in Laos are from villages where post marital residence is with the husband’s family and where women’s freedom to leave a marriage is hampered, for instance by brideprice. Even in these cases, the women who spoke with me displayed an evident attitude that domestic violence was a social ill to be overcome, even if this was mixed still with a good dose of victim blaming.

Great stuff Holly, and loved John? Holt’s connecting what you said about the hard work of mothering to Zen thinking. Loads to talk about but what is your current email address please?