Family economy and mass home ownership in Laos

Chayanov's theory of the family economy helps explain high rates of home ownership in Laos. It also helps explain the sheer drudgery of so much family life in general.

This is part three in a four-part series on near universal home ownership in Laos. Find earlier parts here and here.

When I took up residence on an island in the Mekong River for 16 months back in 2002, a local family took pity and took me in, saying it was impossible to both live alone and complete my research (an observation I came to see as true). I still stay with them when I visit, most recently in 2024.

The house next door to them is abandoned. Actually, that is how we met: I noticed an abandoned house during my first fieldwork and, wanting to live alone, arranged rental directly with the owner (long relocated to the city) much to the shock and gossip of villagers.

Since I moved out twenty-one years ago it has been totally abandoned. Depressing in itself, the ruins block my Lao family’s view of the river and I worry it harbours mosquitos. Thinking money could solve the problem (the same mistake I have been making, on and off, since I first stepped on this island)1 in 2024 I offered to buy it with my Lao family as owners (foreigners cannot own land in Laos). My idea was to demolish the rickety ruins and grow bananas.

Figure 1: My Lao family’s magnificent house in rural Champassak Province (the dilapidated house next door remained out of shot behind me as I took this photo).

When I suggested the plan, though, my Lao family laughed: ‘no one here would sell land!’ Thinking they were out of touch with modern Laos, I insisted that they contact the owner and ask anyway. If he had been willing to breach the local moral economy to rent to me in the first place all those years ago, maybe he would be willing to sell.

Sure enough, he replied that he wanted to keep the house as ‘heritage to show his children.’ The ruins look set to remain indefinitely. When I shared my frustration with my Lao family at his answer, my Lao mother—I’ll give her the pseudonym ‘Mercy’ for the purposes of this post—found common ground with me by agreeing that the owner would be better off donating the construction materials to the local temple. She expressed concern about the accommodation currently offered to monks on the island. If the absentee owner donated the building materials, he would at least gain Buddhist merit, which would surely be more advantageous than letting them rot.

But she stopped short of agreeing with me that he ought to sell the land. She understood his wish. Land is valuable—perhaps the greatest asset of all—but for that very reason on this island it is rarely commodified. Usually withheld from circulation, when land does circulate, it is usually a gift or inheritance.

This attitude is shown in Mercy’s own land transactions. She ran a market garden in the Bolaven Plateau in the 1970s until displaced by American bombing. She stayed in a refugee camp in Pakse at first, then built a town residence she still owned when I first met her. When I asked recently what had happened to that house, she replied she sold it but hastened to add that she donated all the proceeds to the temple, as if she wanted to avert any impression I might have that she made money from the transaction.

Mercy also held significant rice fields when I first met her. After Pakse, she returned to care for her aging mother on the island in 1975 and eventually inherited her mother’s house and fields. Mercy’s husband, without any sisters, also inherited fields on the island from his mother. When I met them in 2002, Mercy’s household was one of the most food secure on the island, despite the relatively large household size: Mercy lived then with her husband, adult daughter, son-in-law and five grandchildren. As these children grew to adulthood, they would need their own fields.

But in the mid-2000s, after the premature death of her daughter, Mercy gave a significant parcel of fields to her niece (younger brother’s daughter), Pheng. On this island, rice fields are usually inherited by daughters, with sons standing to inherit cows and buffalo. Mercy’s younger brother married a local woman, but all her fields were in full use feeding their younger children when their eldest daughter started her own family. When I met Pheng in 2002, she, her husband and their four children lived in a bamboo shack and laboured on other people’s fields in return for rice. In one of the most searing experiences of my first fieldwork, I was there when Pheng’s child died of malaria, the girl shaking, eyes glazed, prone in her father’s arms. We all felt so helpless.

In my most recent visit in 2024, many years after Mercy’s gift of fields, Pheng was living in a large, well-appointed house. She showed me pictures on her smartphone of her surviving children—fully grown now and all working in Thailand—and the holiday she took there with her husband. Her husband is now a card-carrying member of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party and Village head. There is no doubt that Mercy’s gift of land was a key part in this family’s dramatic change of fortune.

I believe Mercy’s gesture was both generous and rational, and it tells us a lot about the value of land in rural Laos. Of course Mercy’s gesture was a gift, and came with the usual deepening of social ties. But more than this, her gesture was based on a particular valuation of land. In general, value in rural Laos is influenced by the importance of the family economy. In the previous post, I identified the family economy as an important policy direction in Laos. Family economy is also an economic form identified and analysed by agricultural economist Alexander Chayanov.

Chayanov synthesised and interpreted the extraordinary findings of a school of Russian economists and statisticians investigating peasant farming, a school he led until his 1930 arrest. This school drew on unprecedentedly detailed data and firsthand observations of peasant decision-making. Lenin had dismissed the importance of the family farm, arguing that it would not withstand capitalism, but facts on the ground proved this assumption too hasty. Chayanov’s school observed capitalist farms breaking down into small peasant holdings because farming families were willing to pay higher than market prices for land.

Chayanov defined family economy as an undertaking aimed at satisfying the demands of household members where household members form the labour force. His archetypal case was a peasant family farm, but he argued that the rationality of the family economy applied to any family enterprise, such as urban artisan activities. The household as both a unit of production and consumption creates an economic calculus where demand satisfaction weighs against the drudgery of labour.

Figure 2: Table from Chayanov’s The Theory of Peasant Economy. Chayanov writes: ‘The curve AB indicates the degree of drudgery attached to acquiring the marginal ruble… The curve CD represents the marginal utility of these rubles for the family farm.’2 That is, CD represents the demands satisfied by family work and AB represents the drudgery of that work.

Chayanov thought of family economy as subjective. Demand depended on customary or social standards that varied. Likewise, drudgery depends on context. When labour is already stretched, extra work is onerous. When labour is underemployed, however, labour appeals, assuming it meets a significant family demand. This helped Chayanov explain some otherwise puzzling facts. For instance, peasants in the USSR showed little interest in threshing machines, and Chayanov argued that this was because these became useful at the time of the agricultural year when peasants were otherwise underemployed. By contrast, peasants eagerly purchased technical interventions that eased work at peak periods, such as the reaper, even when the cost did not make sense in classic bookkeeping terms.

I have a lot to say about Chayanov, but let’s get back to the core question that concerns us here, which is the price (or lack of price) on land in rural Laos. Chayanov discussed the value of land quite a lot, arguing that peasant households without enough land experience underutilisation of labour and unmet needs at the same time. More land could solve both problems at once, making land very valuable to such families. For a household with ample land, where labour is already fully extended and customary needs are met, extra land does not hold the same value. This leads to a paradoxical outcome where the poorest peasants are willing to pay the most for land, and the richest peasants the least.

This helps explain Mercy’s thinking when she divided her rice fields with her niece. Giving away some fields reduced drudgery for her family in the peak of the rainy season. I joined that family for the rainy season transplant in 2024, well after Mercy’s gifting on of a significant parcel of land, and still her household had to call in relatives to complete this critical work in the right time frame. More fields would have made this part of the year even more irksome, and for what payoff? Mercy’s family today still has ample rice.

Over the years I have known them, they acquired first mains electricity and then appliances—phones, washing machine, television and refrigerator—but perhaps most profoundly an electric water pump. The pump reduces daily drudgery (water piped to the house) and allows a second rice crop in the dry season (water to the fields). The dry season previously saw Mercy’s household labour under-utilised, but irrigation combined with Mercy’s gift of land to Pheng spread the drudgery more evenly throughout the year while still satisfying household demand. The one parcel of land was at once of inestimable value to Pheng’s family while also being somewhat irksome to Mercy’s family. The gift was generous, but it was also rational. The land transfer made sense, but no price could be fixed to it.

As a feminist and a mother, I find myself very taken with Chayanov’s idea of an economic rationality that starts with the family and ends with drudgery. Drudgery. What a great word. Translators of Chayanov’s works explain that the original Russian word Chayanov used, tyagostnost’truda, could be translated as ‘irksomeness’ or ‘wearisomeness’ but that drudgery is the closest and shares etymological roots with the Russian original.

“it is possible to make a feminist reading of Chayanov’s theories to explain why domestic work always feels too much and never enough.”

When I was a new mother, about 12 months in, my first born was eating solids and mobile. As much as I wanted to share in his joy in exploring (and tasting!) the world, the constancy of procuring, preparing and placing food before him, and cleaning up the ensuing chaos, all the while trying to keep him safe and merry floored me. In my career up to that point, I considered myself a hard worker but mothering was another form and intensity of labour. I was trying to articulate this to my friend, Danielle, probably using way too many words, when she summed it up in one: ‘its drudgery.’ Danielle, with children older than mine, knew well the costs and benefits of family life. In Chayanov’s terms, my household had gone from a 1:1 scenario (I was one labourer satisfying the demands of myself as my household’s only consumer) to a 3:2 scenario (my husband and I satisfying our needs plus those of the baby). Even though I was on maternity leave and my household now had one extra adult worker compared to my single days, my overall drudgery had increased from 1 to 1.5.

What I love about the word drudgery is that it sums up how not all labour is made equal. The capitalist mode of production, as Marx showed, is premised on the idea that money creates an equivalence between commodities, including labour, so that calculations of profit and loss can be made on the basis of exchange value. But in a family economy, such equivalences are resisted. As every parent knows, when it comes to ‘satisfying the demands’ of young children it is often this particular toy and no other, this exact meal and not the very close but crucially different alternative, and this one very special person to offer comfort and cuddles, no one else. The particularity of demand satisfaction in a family seems related to the sheer drudgery of the very labour aimed at meeting those demands.

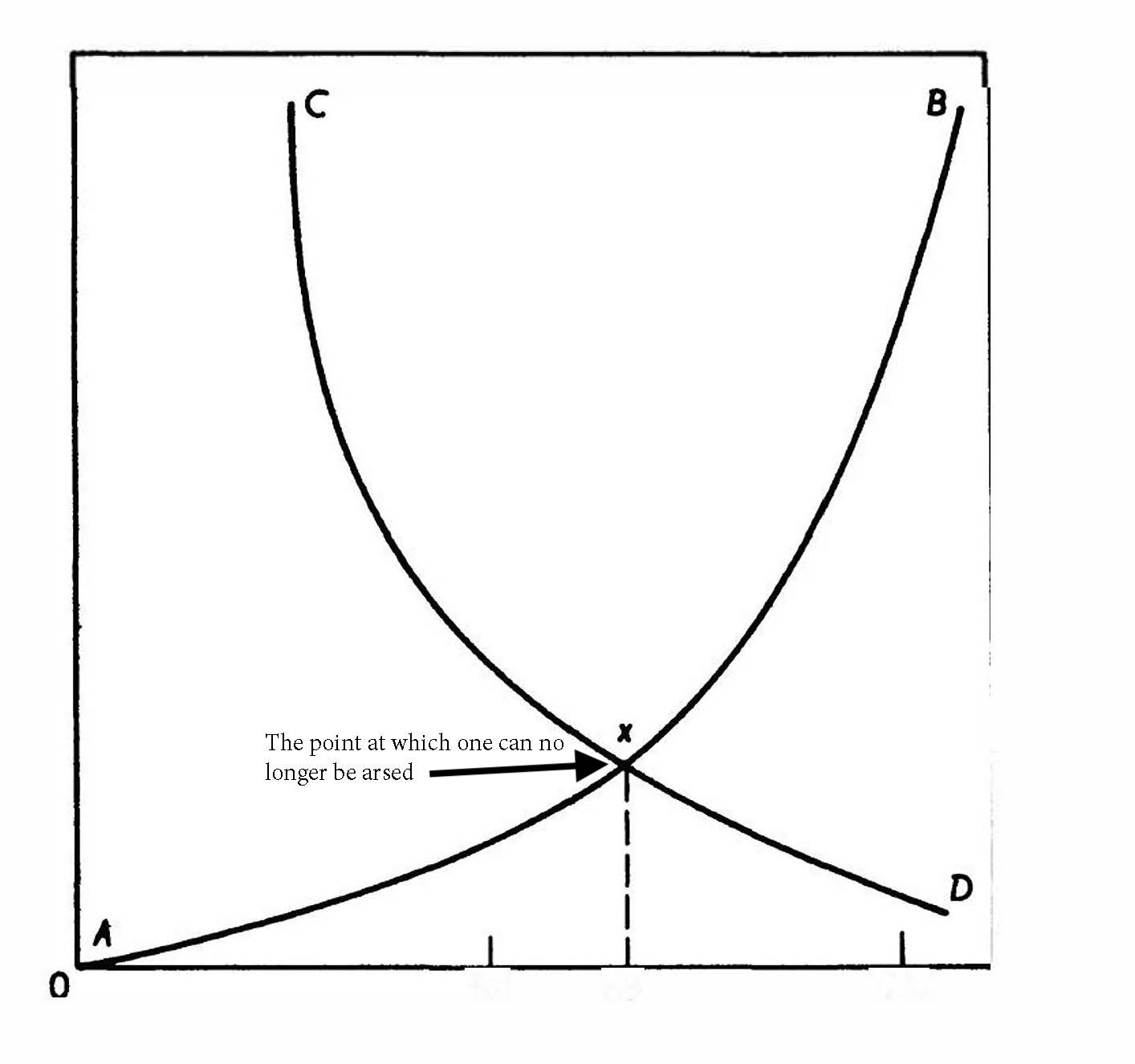

Although Chayanov did not take his economic thinking in this direction, it is possible to develop a feminist reading of his theories to explain why domestic work always feels too much and never enough. In putting reproductive labour at the heart of his economics, he models what happens when the main goal of an economic unit is demand satisfaction for the members of that unit themselves, plus their dependents. His conclusion is that labourers in a family economy self-exploit, often carrying out activities that a capitalist enterprise could not make profitable, but family workers will also sometimes choose idleness over greater production. The equilibrium point is reached when demand satisfaction no longer outweighs the drudgery. Said differently, equilibrium comes when the family worker can no longer be arsed.

Figure 3: A bastardised version of Chayanov’s curve, where AB represents the drudgery of meeting household demands, and CD is the satisfaction that comes of having those demands met, and x is the point where you can no longer be arsed.

For me, I remember hitting x when my first son was weaning. We had a plastic splash mat catching the mess under his highchair. After a feed, I’d take the mat outside to scrape the food off for the chooks. We were living in an off-grid country house at the time. One day I took that mat outside and threw it away. I remember watching its yellow pattern flutter as it caught the breeze and drifted off. This wasn’t a premeditated or even particularly conscious act, but I felt a surge of joy as I watched that filthy mat float away, a joy discordant with my usual passion about plastic pollution (my partner later went and picked it up). The moment felt like freedom and failure at the same time. I take this to be Chayanov’s notion of equilibrium in the family economy: the point where you stop demanding more of yourself.

Often we think of equilibrium as a sort of happy balance, like the bitterly evoked ‘work-life balance.’ But for Chayanov, equilibrium is a tipping point. It’s the hinge where a household labourer flips from caring deeply and working hard (much harder than a waged employee ever would) to having no more fucks to give to a given situation.

Another example is the value of wood in old Kandon. When I was visiting a newly cleared swidden by this remote, upland ethnic Kantu village, I noticed numerous felled trees and asked what these would be used for, knowing that collecting firewood is a onerous but pressing chore that weighs heavily on women. I often see pregnant women carrying entire logs balanced on a shoulder up steep slopes to the village. The man showing me round replied that it depends on how close the log is to the village. If it is far, the wood is left to rot. This fits with Chayanov’s notion of equilibrium between demand (wood for cooking and warmth) and drudgery (the difficulty of bringing wood to the home). When demand is not yet met, firewood’s value sits so high that strenuous (even dangerous) drudgery goes towards procuring it. But when demand is satisfied, the drudgery is such that the wood has no value and is left to rot in place. Chayanov’s theory includes explanations both of extreme self-exploitation of household labour and (when needs are met) underutilisation of resources.

This is the point anthropologist Marshal Sahlins missed when he brought Chayanov to the attention of Anglophone anthropologists in his influential 1974 book Stone Age Economics.3 Sahlins described what he called ‘Chayanov’s rule’: that household labour is inversely related to household production per labour unit (that is, the fewer labourers there are in relation to dependants, the harder they work to satisfy household demand), so therefore the more labourers present the less they work. Sahlins was trying to shake any easy assumptions that classic liberal economic reasoning applied everywhere and anywhere, so he gleefully recounted Chayanov’s argument that, at some point, the peasant family farm will choose idleness over greater production and that resources in a peasant economy are frequently under-utilised.

I don’t disagree with Sahlins’ overall argument, but he errs in downplaying the importance of drudgery in Chayanov’s theory. Sahlins is anthropology’s equivalent of the husband who comes home to his exhausted wife, looks at the messy house and unwashed children, and asks ‘what exactly do you do all day?’ Sahlins sees the moment when maximum drudgery has already been reached and the household worker chooses idleness instead of greater demand satisfaction. He does not acknowledge the intense self-exploitation and drudgery that led up to that point.

Chayanov’s notion of equilibrium in the family economy: the point where you stop demanding more of yourself.

What does all this mean for explaining why almost all homes are owner-occupied in Laos? Housing is a key part of the family economy in Chayanov’s sense. It is extremely valuable to those who otherwise have no shelter, and rural residents in Laos go to great lengths of drudgery and self-exploitation to obtain a home. But for those already adequately housed, extra housing represents only extra drudgery with no extra demand satisfaction.

Needless to say, this is in contrast to the ‘asset economy’ approach to housing that is currently causing so much wealth and misery in the UK, Australia and other settler-colonial countries in the present day.4 The asset approach to housing turns family homes into speculative investments in an uncertain (but almost certainly heavily indebted) future. It turns many home-owners into ‘the bank of mum and dad’ and shuts many younger people out of their society’s usual route to material well-being.

As important as the asset economy approach is in explaining the housing crisis in Australia and many other places in today’s world, the Lao case shows that other forms of housing economics do exist in our world. Just as in Chayanov’s day, today too we can say that non-capitalist forms of economic reasoning exist in the world we currently inhabit. These alternatives are not mere relics of a former age. They are part of our contemporary moment, both in national housing statistics in Laos but also in domestic dynamics much closer to home. In both Laos and Australia, home is where we live and raise children. As spaces of everyday life, homes are where our collective futures are made. Understanding Chayanov’s theory as a general theory of family economic thinking suggests our futures are not always forged in capitalist thinking.

High, Holly.“Ethnographic exposures: Motivations for donations in the south of Laos (and beyond).” American Ethnologist. 37, no. 2 (2010): 308-322; High, Holly. “Melancholia and Anthropology.” American Ethnologist 38, no. 2 (2011): 217–33.

Chayanov, A.V. The Theory of Peasant Economy. Translated by R.E.F. Smith, Christel Lane, Dr and Mrs Stephen Clarkson, Edited by Danial Thorner, Basile Kerblay and R.E.F Smith. The American Economic Association, Homewood Illinois, 1966. Page 82.

Sahlins, Marshall. Stone Age Economics. Routledge Classic Ethnographies. London and New York: Routledge, 2004. p87.

Adkins, Lisa, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings. The Asset Economy: Property ownership and the new logic of inequality. Newark, UK: Polity Press, 2020.

Fascinating reflection, especially articulated so well from a feminist perspective! The discussion of drudgery and self-exploitation go some distance in explaining ambivalence to me as a rival disposition to ambitions connected to the ethic of "hard work." But it also made me think in terms of a radical juxtaposition, about my Japanese Buddhist friends who try to deal with drudgery existentially as a potential form of meditation leading to heightened awareness of everyday life! And here I am thinking especially about Hakuin, the 17th c. patriarch of Rinzai Zen, whose autobiographical "Wild Ivy" (translated in EASTERN BUDDHIST [1983] is also fused with a moral command to find value in the apparently mundane. A contemporary read of this line is Kaoru Nonamura's best selling (in Japan) "Eat, Sleep, Sit (Kodansha International, 1996). Thanks for this great read, Holly. Took me way beyond my urban Luang Phrabang memories and also led to this comparative rumination!!